70 Years After School Segregation Was Declared Illegal, It's Back

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court declared "separate but equal" unconstitutional. Seven decades later, many of the gains in dismantling racial segregation in schools have been lost.

Last Saturday, May 17, 2024 marked the 70th anniversary of the historic 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision that declared school segregation unconstitutional.

In the his majority opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, “We conclude that in the field of public education ‘separate but equal’ has no place, Separate educational facilities re inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

In the years that followed, public schools in the South as well as the North were largely integrated despite sometimes stubborn resistance and even violence.

In recent years, many of those school systems have re-segregated.

“Since Brown we’ve had 10 Presidents, enacted the most important civil laws in U.S. history, seen many barriers fall, but we’re far from the seemingly simple goal of Brown. In fact, we’ve been going backward for more than three decades toward greater degrees of separation - and the separation is double separation, by both race and poverty,” wrote UCLA law professor Gary Orfield, an eminent civil rights law scholar, this month in an essay, The Dream of Integration & the Politics of Resegregtion: The Continued Battle over the Legacy of Brown v Board of Education.

In 2022, I wrote about school resegregation and spoke to Orfield. On the occasion of the anniversary of Brown, I have re-posting it below. It has been slightly edited from the original version.

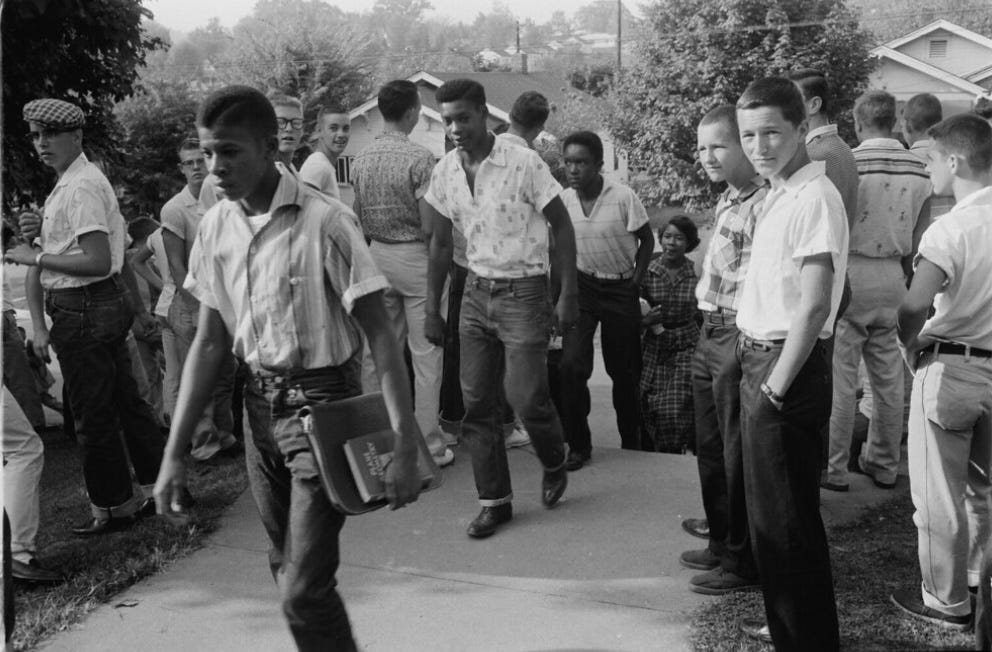

Integration of Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957 photo credit; pqgw

As summer winds down, public schools across the country are reopening. Children from first graders to high school seniors are returning to the classroom. Many of them — 9 million by one estimate, one in five American schoolchildren* — will be returning to schools and classrooms that are largely segregated by race and ethnicity.

It has been 68 years since the U.S. Supreme court’s historic Brown v. Board of Education decision that banned racial segregation in schools as unconstitutional (and, not incidentally, declaring ostensibly separate-but-equal schools as unlawful, unfair and especially harmful to Black children.

Today, legal school segregation as it existed throughout the South is gone, thankfully a relic of a long, dark chapter in American history. But what we have now in many cities and suburbs, counties and rural areas is something that looks a lot like it. It's the result of school resegregation. And it is legal.

In a 2019 report for the Learning Policy Institute, Janet George and Linda Darling-Hammond wrote, "Since the high point of school integration in the 1980s, the share of intensely segregated non-White schools (those schools with 0-10% White students) more than tripled in the United States."

Many Black, white, Hispanic and Asian-American children attend schools that are overwhelmingly or, in some cases, exclusively of one race. In the largest urban school systems — including New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Detroit, Philadelphia, Dallas — minority enrollment is 90 percent or higher. The most segregated school districts in America are not in the South but in Northern cities, many of them bastions of professed political liberalism.

"New York State has the dubious distinction of being one of the most segregated public school systems in the nation," Shino Tanikawa, former member of New York City's District 2 Community Education Council and the School Diversity Advisory Group, told me.

Elizabeth Eckford was chased away from Central High School by angry whites when she showed up for school in 1957. When I interviewed her years later, she recalled with her voice trembling, "I thought they were going to kill me."

The "Little Rock Nine" integrated the school a few days later, escorted by federal troops called in by President Eisenhower to escort the nine Black girls and boys past mobs of angry whites.

Central H.S, 2021 photo credit: Ron Claiborne

Today. Central High School is far more diverse than, say, Boys and Girls High in Brooklyn which has a 94 percent minority enrollment.

Almost invariably, students in segregated urban schools come from poor families and live in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. They are segregated not just by race and ethnicity, but by socio-economic status -- with real consequences, according to George and Darling-Hammond.

"Racially and socially isolated schools often lack resources, such as access to advanced placement coursework or updated technology that can impact student outcomes," they wrote.

It was not supposed to be like this.

To gain some understanding of how we got here from the promise of the landmark Brown decision, I spoke to Gary Orfield, executive director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA and for five decades one of the leading authorities on the history and effects of school segregation. He has been an expert witness or special master in more than three dozen class action civil rights cases involving school desegregation and housing discrimination.

What follows is an edited excerpt of our recent conversation.

RC: In 2019, you wrote that "the promise of Brown is at grave risk." That was three years ago. Is that still the case?

GO: The pandemic has really intensified the racial inequalities. Because the segregated high poverty schools that we write about were just totally unequipped to deal with the pandemic. So the racial gaps in learning have expanded considerably and a lot of people with choices have abandoned the regular public schools because they didn't provide much during the pandemic.

Integration of Clinton High School, Clinton, TN, in 1956. The 12 Black students were met by an angry, jeering white protestors. Two years later, the school was bombed and destroyed. photo credit: plumsplomb

RC: Please take me through the history of segregation, desegregation and resegregation. We know that before Brown what the situation was in 17 Southern states (legal segregation as permitted by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson separate-but-equal decision by the U.S. Supreme Court). In Northern states, in cities like New York, Chicago, San Francisco, what did the public schools look like racially?

GO: They were extremely segregated.

RC: Based on housing patterns?

GO: Based on housing patterns and all kinds of intentional actions by the local school authorities. So basically every single case we had tried in the Northern and Western school districts proved that history of intentional segregation in terms of site selection, of zoning, the assignment of teachers, the assignment of special curricula. There's a range of things that were done. In many of our Northern cities, we actually created freeway systems that separated people by race and eliminated outlying areas of minority settlement. None of this happened by accident. It was very intentional. There really is no de facto segregation. Almost all of it involved intent.

RC: In terms of schools, Brown came along and desegregation started to occur in the late 1950s, 1960s?

GO: What happened after Brown, we had massive resistance in the South. Nine years after Brown, 99 percent of Black kids in the South were in 100 percent segregated schools. There was very little progress. Nothing really happened to significantly integrate schools until the Sixties when the Civil Rights Act was passed and the Johnson Administration actually enforced it. It was the only civil rights law that was ever seriously enforced. The South went from 99 percent segregation to become the most integrated part of the country. You can do something about stuff, but you can only change it if you're serious about changing it. Use incentives and sanctions. They did it and it lasted for a long time. It lasted until the Supreme Court dismantled it in the early 1990s.

Anacostia High School, Washington, D.C. was integrated in 1956. photo credit: Washington Area Spark

RC: What was happening in the North, meanwhile?

GO: The Supreme Court didn't say a word about segregation outside the South until 1973 in a case from Denver called Keyes. In that case, they said you can give desegregation orders in the North but it's going to be really hard because you are going to have to prove the segregation was intentional. The next year (in Milliken v. Bradley) from Detroit, the Supreme Court said you have to leave the suburbs alone.

[Jon Hale, a professor education now at the University of Illinois, said about the Millikin decision: "(It) sanctioned a form of segregation that has allowed suburbs to escape being included in court-ordered desegregation and busing with nearby cities. The Millikin decision recognized 'de facto' segregation -- segregation that occurs as a result of circumstances, not law. This allowed schools in the North to maintain racially separate schools at the same time Southern schools were being ordered to desegregate. By giving suburbs a pass from large mandated desegregation attempts, it built a figurative wall around white flight enclaves, essentially shielding them from the 'crisis' in urban education."

In his dissent, Thurgood Marshall (the only Black justice on the Supreme Court at the time) said the result would be tragic for millions of kids. Since then, we really haven't been able to desegregate metropolitan areas. By the time the Supreme Court said you could desegregate the North, many of the central schools were already predominantly non-white and there weren't really feasible answers inside the central cities.

RC: Where were the white students going?

GO: Many were going to the suburbs ever since World War Two when the federal government through the VA and the FHA made it possible to develop suburbia on a mass scale for whites only.

RC: But you say segregation declined heavily with respect to Black students from the Sixties to the early Seventies.

GO: No. Till the late 1980s.

RC: Then what happened?

GO: It was stable until about 1988. Desegregation was a pretty durable reform when it was done decently. It was intentionally dismantled by the Supreme Court in 1991, 1992. [The 1992 Dowell decision, decided 5-3, essentially said desegregation plans meant to redress past intentional racial discrimination could be ended even if it resulted in resegregation.]

RC: So, the trend since then has been…

GO: Significantly greater segregation all over the country. The dismantling of all the major desegregation plans. The trend has been a steady process of increasing segregation. Part of that is demographic because we've had a very dramatic decline in the white birth rate and huge immigration of Latinos and Asians. But part of it is because all of the desegregation plans that we've had have been shut down.

RC: A significant difference is, in the early Sixties, the percentage of Latino students (nationally) was miniscule and now we're seeing Black and Latinos often being the large majority in public school systems in big cities.

GO: People still think about he Black-White issue in the South as the epitome of the Civil Rights issue. The South now has more Latinos than Blacks even though most Blacks in the country are still in the South. And the West has about one-twentieth Black students and it is becoming predominantly Latino.

RC: In one of your studies you say that whites and Latinos are the most segregated groups.

GO: Yes. They both are isolated and Blacks are becoming less concentrated with other Blacks. It's extremely so in the West and Southwest where they basically tend to be Latino schools. The Black middle class has moved massively to the suburbs. There's very little Black middle class in a lot of our central cities. So you have class segregation on top of race segregation.

RC: There's an expression in your studies, intense or intensive segregation. What is that exactly?

GO: That's a case where there's zero to 10 percent white students in a school.

RC: Are we seeing more of that?

GO: Yes. and we're seeing more of what we call apartheid schools which is zero to one percent white students in a school.

RC: What are the consequences for Black, white, Latino, Asian students. when you attend a segregated school? What does it do to the students?

GO: If you're attending a school that's segregated, Black and Latino, the chances are you are attending a school that's at least two-thirds poor kids too. Poverty dominates that school. That produces housing instability. It produces concentrated health problems. It produces developmental problems. The likely exposure to crime. It produces a more unstable housing market. It produces a lot of negative influences. It tends to produce disinvestment and departure of jobs. It's a very destructive process.

photo credit: monkeybusinessimages

RC: If there is even the will to do so, what will it take to change this trend line toward greater segregation?

GO: It will take a decision that we want to change and we realize that it won't change by itself. The default in our society is segregation. Our society was built on discrimination and segregation in very important ways. If we are going to change we have to decide to use the tools to change it. The first thing we should do are the voluntary tools that say we will foster more magnet schools that are going to be intentionally diverse. That's how colleges get to be diverse. They're only diverse when we intend for them to be diverse, and create the machinery for it to happen.

If we really jumped on real estate practices that steer people by school districts and by racial composition of schools. That would be a very positive force. We have to pull a lot of levers because there are a lot of levers that are built into the segregation system. But we could do it and we would get good results. We wouldn't stop the whole problem but we would at least create opportunities for millions of people that don't exist now.

We're getting more and more powerful research that shows the benefits (to diversity in schools) and to show there's no real cost for the white students who are involved. That's a pretty consistent finding for a very long time now. So, we're finding it's more and more beneficial and we're doing less and less about it.

* The estimate of 9 million children attending mostly segregated schools comes from a non-profit, EdBuild, that describes itself as an organization advocating for "common sense and fairness to the way states fund public schools."

Amazingly, some folks-in Alabama no less- believe that a diverse student body is quite desirable:

https://eji.org/news/charter-school-becomes-first-racially-integrated-school-in-sumter-county-alabama/

If you have the emotional energy, would you consider writing a new piece about the pressure on colleges to abandon race based admissions? I know it’s a complicated and messy thing snaking its way through previous gains. We have a classmate you could interview as an expert. - CG