CONFESSIONS OF A CAMPAIGN CANVASSER

I spent eight days canvassing for Kamala Harris in four states. Did it matter?

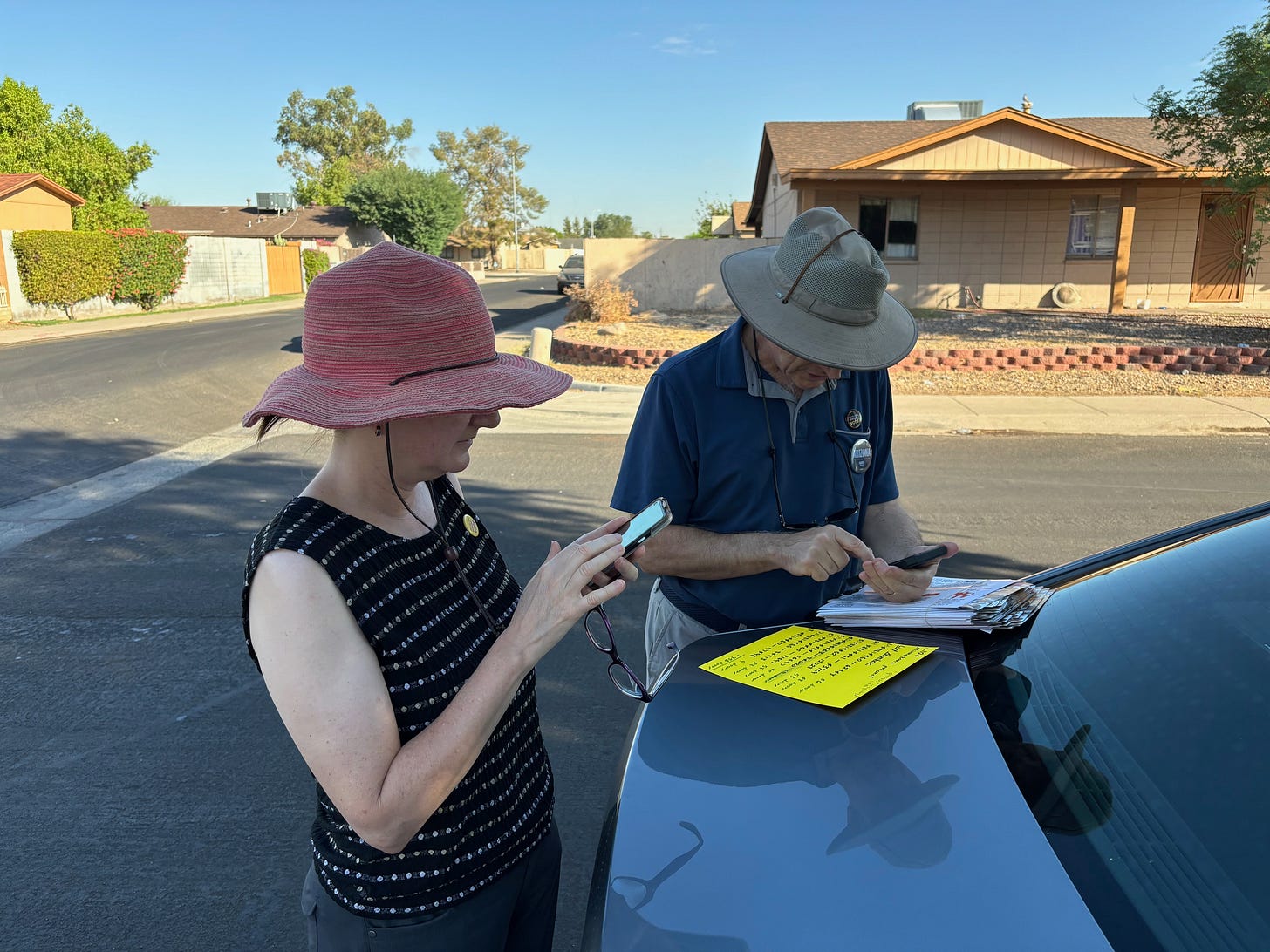

Canvass colleagues in Phoenix

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA

I step up to the door. There’s a bell I could ring but we’ve been taught that knocking is better. I knock on the door frame. I wait about 30 seconds, knock again, and take a step back. I clutch a clipboard in one hand, my cell phone in the other. I’ve memorized the names of the couple that lives at this address. From the app I have on my phone, I know their age and their party registration. I fix a bland smile on my face just in case they look through the peephole to see who could be at their home on a weekday holiday. I hear the sound of movement from behind the door and wonder once again how I will be greeted: Friendly? Curiosity? Suspicion? Hostility? You never know.

The door opens. It is a white man in his 70s. He's dressed in short pants and a tee shirt. A woman - I know from the personal info it must be his wife - is standing a couple of feet behind him, peering at me. I read their expressions. They’re curious but genial. That’s good.

I quickly give my name and explain that I’m canvassing on behalf of Kamala Harris, Dr. Amish Shah, who’s running for the House in this Republican-held congressional district, and a statewide abortion rights referendum. I watch carefully for their reaction. Their expressions signal solidarity. Good. This won’t be a heavy lift.

I ask if “we” can count on their support. Oh yes, the man says, we're voting for Harris, Amish, the referendum. Have they received their mail-in ballots? They say they have. Now comes the tricky part. Ideally, we want to persuade them to fill out the ballot right there and mail it immediately at the nearest post box. I know from checking there is one attached to the apartment building's mailboxes not far away. The idea is that’s a vote we know for certain has been cast. But, as I anticipated, I can tell they find this overture a little too pushy. They say they’ll be mailing them tomorrow. As I have been trained to do, I try again: “If you do it now, it’s done and you don’t have to think about it again.” The couple remain polite but firm. They'll do it tomorrow. I could press the issue - we were trained to try three times - but I know it won't work and would risk being rude. Some things I won't do. I thank them and leave, pausing to enter their answers in the app: "Strong" for Harris, Shah and referendum. Did not fill out a ballot in front of me. Plan to mail it later.

I move to the next apartment and do it all over again.

Canvassers, Phoenix

This was my second day in the Phoenix area canvassing. The day before, I was in a Latino neighborhood in South Phoenix, door knocking and promoting Harris, the local House candidate there and a woman running for district attorney. Most people weren't home - three out of four - but among those I did reach, the reception was favorable but that's no surprise. It's a heavily Democratic neighborhood.

Phoenix

DOES CANVASSING WORK?

I am a foot soldier in the army of volunteers door knocking for Kamala Harris and sometimes candidates for down ballot offices. I’ve read there are thousands of us doing what I’m doing in the key states that will decide the upcoming presidential election. Arizona. Nevada. Wisconsin. Michigan. Pennsylvania. Georgia. North Carolina. In most places, the voters who are targeted by the Harris and local Democratic candidates are registered Democrats. Sometimes independents are canvassed. Republicans are not.

Canvassing is part of the so-called ground game of political campaigns, as opposed to the air game which is television and internet ads. The ground game includes door knocking, phone calling and mailing campaign literature or postcards. The conventional wisdom is that door knocking - face-to-face encounters - are the most effective ground game. The idea, simply put, is that people are most likely to respond to people they interact with face-to-face, ideally through a conversation rather than a perfunctory few rehearsed lines. But there's actually not a lot of data to support the theory. In fact, some data I found undermines it.

In the latest (2019) edition of their book, Get Out The Vote!, political scientists Alan Gerber and Donald Green estimated that the average per-conversation effect of canvassing was 4.0 vs. 2.8 for volunteer phone bank calls, which essentially means that 5,000 doors knocked with 1,000 people responding (a rate that is roughly what I experienced) yields 40 new voters vs. 28 from phone bank calling. That's not a lot. And while canvassing is, according to these researchers more effective, a volunteer can reach far more people than walking from house to house.

Two other researchers - David Brockman of UC Berkeley and Joshua Kalla of Yale - concluded that the ground game generally is largely ineffective in persuading people to vote for a particular candidate in general elections (but better with primaries). It can be effective though in getting voters to actually go to polls and vote. It is that theory that led me to canvas. This presidential election will turn on who can get their voters in key states to vote. Face-to-face interactions can help do that, and inform voters about how and where and when they can vote.

Door knocking in Detroit

DETROIT

My first canvassing experience this election year was in Detroit where I arrived on the last day of August. Michigan went narrowly for Biden in 2020 and even more narrowly for Trump in 2016. Detroit, with a majority Black population, is deep blue and the key to Democrats winning the state (so blue that in 2020, Trump fraudulently claimed election fraud there). For Democrats, the goal is to boost that turnout in and around Detroit.

I reported that morning to Henrietta Ivy, the local volunteer coordinator, a genial, voluble woman who was operating out of a storefront in an area of Detroit that was utterly unfamiliar to me. Henrietta was warm, gracious and boundlessly enthusiastic. She paired me with the one other volunteer there that day, Carolyn, a local woman, and quickly taught us how to use the app loaded with names and addresses (and ages) of registered Democrats on our assigned turf and dispatched us. It was a neighborhood of small homes about a mile away. Before we left, Henrietta emphasized the cardinal rule of canvassing: Do not walk on people’s front lawns.

Henrietta Ivy, Detroit

Because early voting hadn't even begun, our primary task was to get answers from voters to questions about what issues were most important to them. Secondarily, we were to promote Harris and the Democratic candidate for Senate, Elissa Slotkin. If no one was home, we were to stuff campaign flyers in their door (but not mailbox. Evidently, that’s a federal crime). The issue responses would be crunched by someone somewhere to help shape the campaign’s future state campaign strategy, but I could easily imagine it sharing the fate of the ark in the movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, shelved and forgotten in the bowels of an enormous warehouse.

At more than half the homes I went to, no one answered, even homes where the front door was open and sometimes I could hear people talking, music playing or, on several occasions, smell marijuana being smoked. I really couldn’t blame them. Who knocks unexpectedly on your door on a weekend afternoon? Bill collectors? Solicitors? Police? Chances are if someone comes to your door who you aren't expecting, it isn't someone you want to see. If no one is home, we leave campaign leaflets in the door. In canvass lingo, it’s called “dropping lit.” But you wonder if anyone reads it. IN the swing states, voters have been deluged with campaign lit for months.

Of those who did come to the door, almost all of them told me they would be voting for Harris. More than a few volunteered pungent epithets about Trump. One man, who looked to be close to 80, told me he was voting for Harris because “I’m a Vietnam veteran. Trump hates me. He hates veterans.”

I noticed that generally the older people were, the more vocal and politically aware they were. Younger people - those in their 20's in particular - were hardest to read. They tended to be unresponsive, often looking at me with studied indifference or muttering unconvincing pledges that, yeah, they would vote. On balance, support for Harris that I heard was quite strong. I was encouraged.

But there were exceptions. An older Black woman and her adult daughter said they hadn’t decided. I asked how they would make the decision.

The mother said, “I’m going to pray on it the night before Election Day.” Her daughter nodded in agreement. I started to pursue it, but quickly changed my mind, thanked them and left.

At another home, a thin, middle-aged white man in a long-sleeved red tee shirt - the only white resident I came upon in two days - said he was voting for Trump, then offered an unsolicited explanation that sounded like Covid vaccine conspiracy nonsense - I wasn’t paying close attention. I was just trying to leave. Then he said, “That football player was shot in San Francisco the other day. Kamala Harris was the mayor of San Francisco.”

I said, “Actually, she was the prosecutor, not mayor.”

The man appeared nonplussed.

“You just told me something I didn’t know,” he said.

What surprised me was that when I asked people about the issues or concerns that were foremost to them, few people had an answer. I often had to recite the laundry list and they’d pick one - most often, it was the economy. Several said “to stop Trump,” which wasn’t even on the list.

Some of these doorstep encounters were often brief and perfunctory. But some evolved in pleasant conversations, allowing me to go off script and it became just two people talking. I made a point never to bring up Trump. But if someone did, I didn’t hesitate to concur.

I canvassed two days in Detroit and then flew home. They felt like two productive days.

Pre-canvass briefing in Philadelphia

PHILADELPHIA

Two weeks later, I was in Philadelphia to canvas. Pennsylvania is one of six or seven swing states that will decide the election. It has the most Electoral College votes of the swing states - 19 - and is therefore arguably the most important of them. In 2020, Biden won Pennsylvania by 81,000 votes - over 1 percent - out of more than 6.8 million votes. In 2016, Trump won by 68,000 votes, or 1.2 percent, over Hillary Clinton.

Current polls show Harris and Trump essentially tied. For Democrats to win, they will have to turn out the vote where they’re strongest and that means Philly.

My first day I was assigned to a group of about a dozen. Everyone except one guy who'd flown in that day from San Francisco had been canvassing there for several days. Two women were from California, one from Houston and there were a few New Yorkers. Our team leader was a young man from Philly named Rory who looked to be about 23.

At our orientation in a park near Temple University, we got a crash course trained by Rory. The emphasis here would be getting people to register for mail-in ballots as well as promoting the Democratic slate from President, Senator and Attorney General all the way down the ballot to state treasurer. We would carry with us the forms for mail-in registration but we were told repeatedly not to fill in anything ourselves. Canvassers were strictly forbidden to write on the applications. We were also instructed to be absolutely sure no line was left blank or else the mail-in ballot application could be rejected. It seemed simple enough.

We were asked to introduce ourselves, where we were from and why we were volunteering.

When it was my turn, I said by way of explanation, “This is the most consequential election in my lifetime.”

Someone remarked, “I hear that every election, that it’s the most consequential of my lifetime.” I was pretty sure I was being mocked. I let it go.

After our orientation, we broke up into groups of four and were sent out to various addresses. I drove myself to a residential neighborhood in North Philly. The first address on my list turned out to be a rather large nursing home. There were about 20 residents on the canvas roster. When I went inside, I was immediately assaulted by the cloying aroma of urine and chlorine that, in a Proustian jolt, transported me back to my childhood, when I used to visit the nursing home in Los Angeles that my dad owned for a time.

It seemed like a decent enough facility. There was plenty of staff, most of them chatting casually with one another at the stations on each floor. They ignored me. Most of the residents were Black, but there were a few white people too. Almost everyone was in their bed in the middle of the afternoon, watching TV. I wondered: is this how one is fated to spend their sunset years? Watching television in a darkened room? Most were watching the Eagles football game. Others were lying in bed idly. A few were asleep. I came upon one ancient, skeletal woman propped up in a hospital bed. She appeared bewildered. When I asked for her by name, she stared at me uncomprehendingly, or maybe she did comprehend but was unable to speak. Undeterred, I asked if she had applied to vote by mail. Silence. She watched me closely but said nothing. I started to ask again, then I realized there was no point. I thanked her. As I walked away, I saw her following me with her eyes. I registered her on the app as "unavailable."

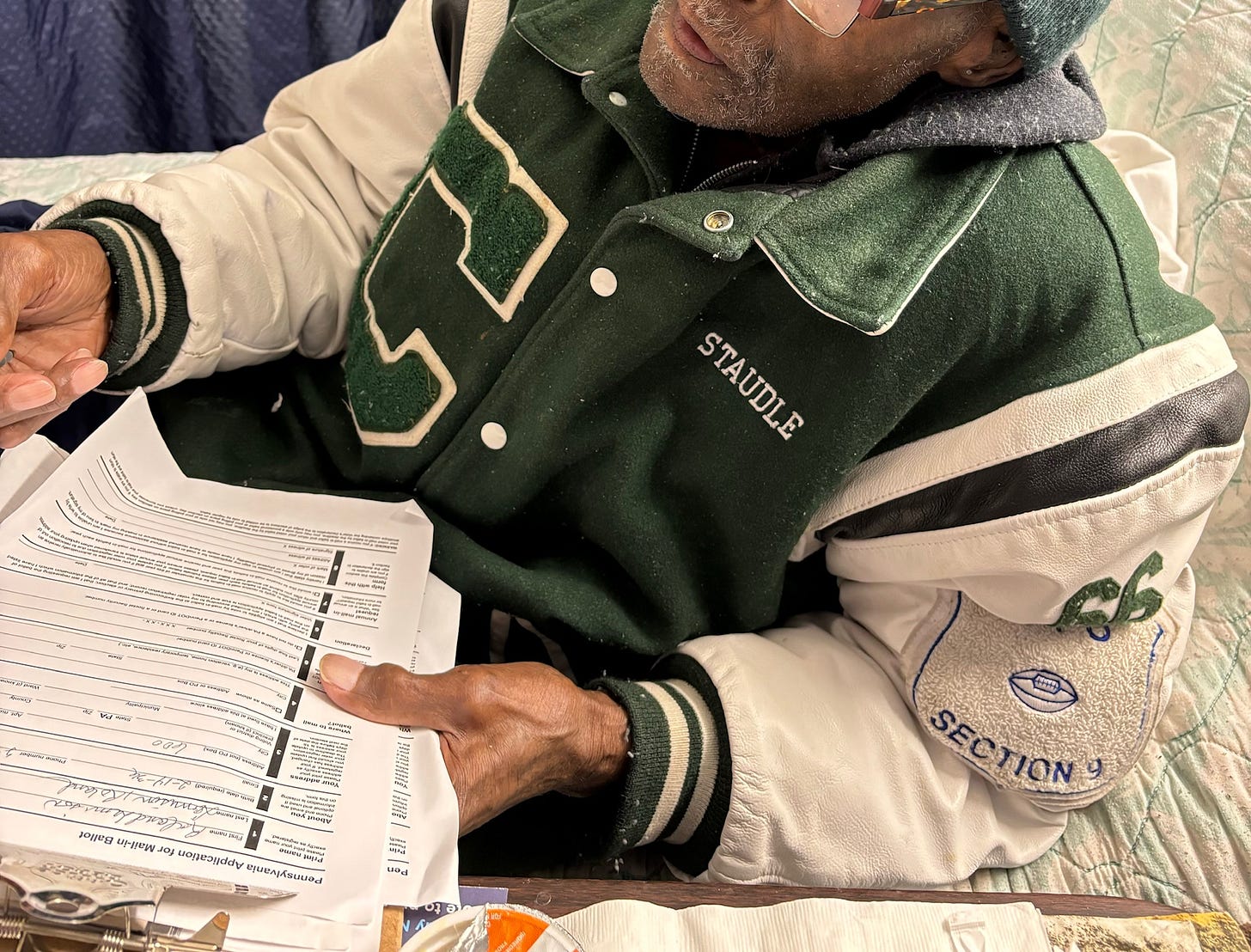

Nursing home resident signs up for mail-in ballot, Philadelphia

Overall, the canvassing at the nursing home went well. Several people signed up for mail-in ballots. Most people at least claimed that they intended to vote the Democratic line.

I joined my colleagues afterward and we combed a working-class neighborhood of modest houses. Again, the response among those who answered the door was positive.

At the end of the day, we met in another park and discussed how our day had gone, what we’d learned, do's and don’ts.

Two women recounted an exchange with a man who told them, “I hope this doesn’t sound sexist but women can manage children. They can’t run a country.”

Someone said, “You should’ve told him about Angela Merkel.”

I just shook my head. No, I thought, citing Angela Merkel or Margaret Thatcher or even Mother Theresa is not going to affect someone who thinks like that.

I returned a week later and canvassed in Cheltenham, a diverse middle-class suburb right next to Philly with a mixture of Black, white and Asian residents. Once again, the responses were generally very positive. I met a young Black man, about 25, who said he was undecided. I had not come across many undecided voters. We had a brief, pleasant conversation. I tried gentle persuasion to no avail. The young man said Trump was coarse and erratic, but he wasn’t sure how Harris would handle the economy. In the end, he completed the form to request a mail-in ballot. Later, I discovered he’d left two lines blank. Rory told me his application would probably be rejected. I hadn't done my job. I vowed not to ever make that mistake again.

That afternoon, I went to a house where I met a middle-aged Black man who, when I inquired, said the most pressing issue for him was abortion. I wasn't sure what he meant. Was he pro-choice or anti-abortion?

“My wife and I," he explained, "we're Christians. I just hate to see a life taken.”

I started to thank him and leave. I figured they certainly would not be supporting Harris. But he wasn’t done.

“But,” he continued, "this election is about who is best qualified to be president and that’s Kamala Harris.”

“Will you vote for her?”

He said, “Yes.”

Billy Griddley canvassing in Mint Hill, N.C.

CHARLOTTE, N.C.

Billy Gridley and I are canvas teammates. On a warm autumn afternoon this past Saturday we were deployed together to a suburb called Mint Hill. I’d never heard of Mint Hill until the pre-canvas lunch meeting of volunteers and canvas leaders on the patio of the Flying Biscuit restaurant. At that briefing, we were told we’d been door knocking at the homes of Democrats, Republicans and Independents. (which is the largest of the three in NC). We would be promoting two legislative candidates and the Democratic nominee for Governor, Josh Stein. We were warned about the possibility of verbal abuse from Trumpers and how to back off. One of our leaders told of a recent canvasser who was shot repeatedly with a pellet gun. That anecdote gave me pause.

Billy is 66, from New York City and recently retired. He’s a bundle of energy, and has a great sense of humor punctuated with bursts of laughter. He’s a veteran of 4 days canvassing in the Charlotte area and, as we made our way through Mint Hill (without incident), wondered aloud if what we’re doing even works.

“I don’t know if I’m making a difference,” he said when we were in the car together having just wrapped up canvassing on a street and heading to another. “I really don’t.”

I said, “Yeah. But we do what we do.”

Billy laughed. “We do what we do,” he repeated.

When we were done for the day, I had a chance to ask him about his canvassing experience, including why he did it.

“This is the first year of my retirement and frankly it’s the highest and best use of my time,” he said.

He drove down a few days earlier and plans to log 13 or 14 days of canvassing despite questioning whether it has any effect.

“I suspect at the margins it must, otherwise I’d get in my car and drive back right now,” he said.

The next day, I canvassed with a different group, one promoting primarily Harris-Walz in a Get Out The Vote effort. It was on the other side of Charlotte in a neighborhood called Sugar Creek. The addresses I was assigned were in a new housing development in what must have been forested land not so long ago. I was told it was quite diverse and tilted Democratic. My targets would be registered Democrats and Independents. I went out solo.

As usual, most people weren’t home. At a few houses, I saw someone peek through the curtains to see who was there. I wore two large campaign buttons to make myself easily identifiable. Whoever it was who was home didn't answer the door. I wasn’t surprised.

I met an octogenarian white woman in her open garage. She had a Southern accent but, chatting with her, she told me with pride that she was originally from Pennsylvania and “I always vote Democrat. But she couldn’t remember if she’d requested a mail-in ballot. I told her she could easily go to the nearby early voting location.

“I’ll get my son to take me there,” she said. I gave her the address. One tiny victory.

At another house, I met an 81-year-old Black woman who told me she was a Democrat and was excited about Harris but wasn’t going to vote.

I was taken aback. “Why not?” I asked.

She said she wasn’t voting because if she did, her votes would be “changed,” by which I assumed she meant changed to a vote for Trump.

I pleaded with her to vote. I assured her it was secure. I said the state could be decided by a tiny number of votes. I detected a French accent and learned she was from Quebec. I tried to make my argument in French, which she seemed to appreciate. It elicited a smile and we spoke in French. But nothing worked. It was dismaying. A lost vote.

At another home, I talked to a young Black man, 20 years old so it would be his first opportunity to ever cast a ballot. I remembered how exciting that had been for me.

He opened the front door, but only a couple of inches. I could only see a sliver of his face, one blank eye, a patch of sparse post-adolescent moustache. He told me he hadn’t decided whether he was going to vote. I asked if he knew who he would vote for, if he did.

“I haven’t decided,” he said.

This bothered me.

“Look,” I said, “It’s going to be Kamala or Trump.” What I meant was: how can you NOT decide between those two options? But I was even more disturbed by his evident lack of interest in voting.

Now I was exasperated and not bothering to hide it. In fact, I wanted him to see it. “People died so I and you can vote,” I said. “Died! It takes five minutes. You’ve got to vote.”

The young man just looked at me blankly.

“Do your research and please vote,” I said. “Thanks.”

He closed the door quietly.

I moved on to the next address. That afternoon, I reached 60 homes over the course of four hours. I had spent eight days canvassing. Did it have any effect? I don’t know. We do what we do.

Thank you for your service to our urgent cause, and for writing this. I’ve been canvassing, too, in Pennsylvania every weekend for the past five weeks. I’ve had mixed results and sometimes feel discouraged except that each time I felt I had met a couple of people who thought twice about not voting, or who needed reinforcement to vote their conscience in a household that was largely Trump. One week I was a bus captain and we went to a very, very rural part of PA that was largely Trump voters. But there were those few who were Harris supporters, including an immigrant from Mexico, likely a farm worker, who is now a citizen and who will vote by drop box because of his work schedule. We made sure he knew how to do that so his vote would be counted. My canvassing partner said to me that we were doing a great deal of good making voters like that young man feel less alone. I think he’s right - let’s remember that sometimes people decide not to vote at the last minute because they feel it won’t make a difference. We know it will and can encourage them. In that same rural neighborhood I got chased off a property by a man with four dogs. I’m glad he didn’t have a gun with him. I felt unsafe. Even so, if you asked me if I’d do it again, my answer would be “ Absolutely, yes.” And in fact, I did go back out again the following week, and I will go again this weekend. Every vote counts. We are making a difference, and I hope we get the result we need.

I hope when canvassing Cheltenham you invoked the name and spirit of the pride of Cheltenham High, Mr October himself, Reginald Martinez Jackson. His presence still carries juice there.