It was the Main Street of Black Los Angeles when L.A. was rigidly segregated

Central Avenue was the African-American community's social, entertainment and economic hub, and only place where Blacks and whites mixed socially. Today it's just another desolate street. Part 1.

Club Plantation in the 1940s. Photo credit: Walter L. Gordon, Jr./William C. Beverly, Jr. collection, UCLA Library Special Collection

There's not much to see on South Central Avenue anymore and there really isn't much to do. It starts in downtown Los Angeles in the Little Tokyo district and runs about nine miles south until it ends in the city of Carson. Downtown, there are some new apartment buildings sprouting up, signs of progress. Otherwise, it's just another dreary commercial street with the usual hodgepodge of establishments you will find in any poor or working class neighborhood in almost any large city in America. Liquor stores. Small sundry shops. Gas stations. Car repair places. Warehouses. Wig shops. Lots of vacant lots. There's a beautiful old Coca-Cola bottling plant along the route. And an old firehouse that is now a museum dedicated to the Black firefighters who worked there when the Los Angeles Fire Department was still rigidly segregated. There are quite a few ancient two-story apartment houses, their facades now faded and peeling from decades in the blistering sunshine. The people you see on the street — yes, some people in L.A. walk — are Black or brown. More Latinos than Blacks these days. If you’re driving with your windows down, you’ll catch snatches of Mexican music blasting from shops or other cars.

It takes a fertile imagination to picture Central Avenue as it once was. More than imagination, you also have to know its story for this street to hold any significance. Like those apartment buildings, that history has faded. About all that's left are the dying memories of the very old, and a handful of physical structures from a time when this street was known as The Avenue, when it was the vibrant, pulsating center of African-American life and culture in Los Angeles.

"By day, it served the community's shopping and business needs. At night, it became a social and cultural mecca, attracting thousands of people from throughout Southern California to its eateries, theaters, nightclubs and music venues," wrote Steve Isoardi in the book, Central Avenue Sounds.

"Central Avenue was it," recalled jazz pianist Gerald Wiggins. "It really was a ball. The town was alive and really jumping. Everybody had fun. It was really some good times."

Central Avenue today

Central Avenue became the Main Street of Black L.A. not by design, or at least not by intentional design. It was the result of racism and the strictures of housing discrimination that were legally sanctioned.

In the late 19th century, when Los Angeles was still not so much a city as a sprawling small town of 11,000 [in 1880]. People lived pretty much wherever they wanted. Whites. Blacks. Hispanics. Asians. Land was cheap and abundant. No one much cared where you made your home.

Downtown Los Angeles in the 1880s. Photo credit: Metro Transportation Library and Archive

By 1890, the city had grown to over 50,000, then to 100,000 in 1900. The population then tripled in the next ten years as California became a magnet for newcomers. Where residential areas had once been integrated, that began to change. Around 1910, white realtors began inserting racial covenants in deeds, specifically prohibiting the sale of property to non-whites. The restrictions soon became the norm, abetted by lenders refusing to loan to non-Whites and white owners refusing to sell to anyone who wasn't also white. By the 1920s, Los Angeles was rigidly segregated, even the "public" beaches. The Black population, about 3% of the fast-growing city, was confined to the narrow strip bisected by Central Avenue.

"We were encircled by invisible walls of steel," said one Black resident who lived in the Central Avenue corridor in 1917. "The whites surrounded us and made it impossible to go beyond those walls."

As more Blacks arrived, the corridor expanded south, though not without resistance - sometimes violent - from white homeowners.

In 1919, the California Supreme Court heard the appeal of a lower court ruling overturning racial covenants in real estate contracts. In a legally and morally perverse decision, the state's highest court ruled that while it was unlawful to forbid the sale of a house based on race or ethnicity, it was perfectly legal to refuse to allow non-whites to live in the house. The invisible walls were now visible, enshrined in law.

When the eminent Black architect Paul R. Williams began his career in L.A., one of the first homes he designed had a covenant so strict it forbade a Black person from even spending the night in it.

Williams would go on to design some of the most famous buildings and homes in Los Angeles. He became the architect to the stars, designing houses for celebrities that he himself could not live in.

In 1937, Williams wrote, "Today I sketched the preliminary plans for a large country house which will be erected in one of the most beautiful residential districts in the world ... Sometimes I have dreamed of living there. I could afford such a home. But this evening ... I returned to my own small, inexpensive home .. in a comparatively undesirable section of Los Angeles. Dreams cannot alter facts. I know ... I must always live in that locality, or in another like it, because .. I am a Negro."

As the Black population grew, there was really only one place for them to go. The Central Avenue corridor.

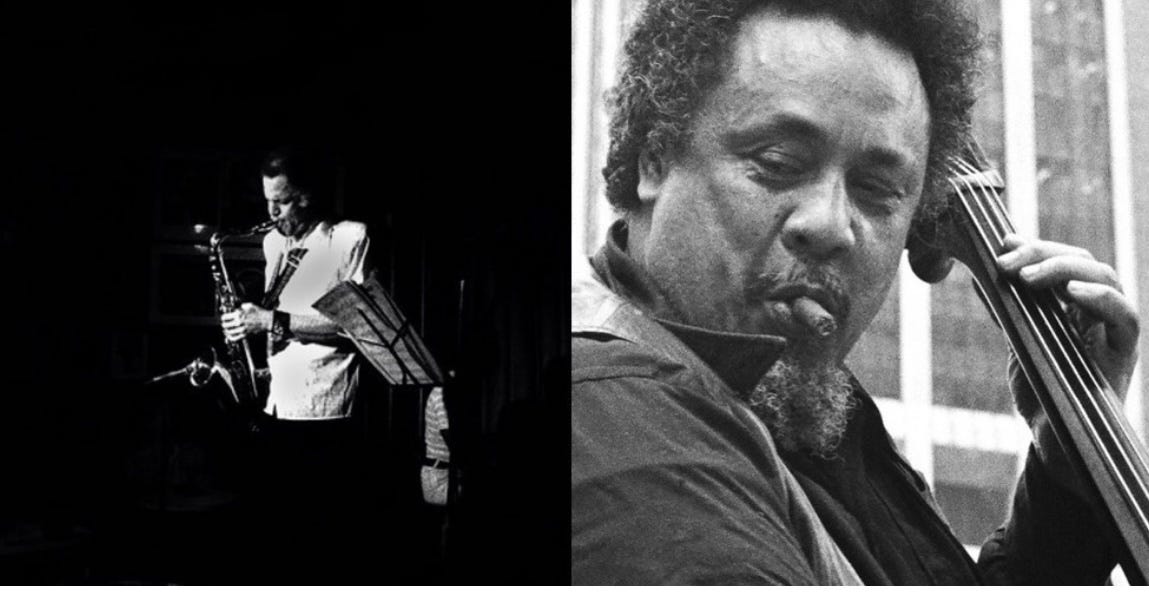

Jazz first came to Central Avenue early in the century, brought by New Orleans musicians who moved there. By the 1920's, Central Avenue was in full swing. Its clubs and ballrooms drew some of the greatest musicians in the history of jazz. Duke Ellington. Louis Armstrong. Count Basie. Coleman Hawkins. Lester Young. Billie Holiday. Charlie Parker. Nat "King" Cole. The clubs also showcased young local talent such as Dexter Gordon and Charlie Mingus, graduates of Jefferson High School, the local high school where they studied under the legendary music teacher Samuel Browne. White jazz musicians, like Art Pepper, played the Central Avenue jazz circuit too, in integrated bands, something almost unheard of elsewhere.

Club Alabam in the 1930s. Photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library

Along Central Avenue, there were dozens of clubs. Club Alabam. The Downbeat. Ivie's Chicken Shack. Jack's Basket Room. Elks Hall. Dynamite Jackson's. The Jungle Room. The Plantation Club. The music and the partying went on literally all night every night. On weekend nights, the streets would be clogged with people of all colors, dressed up and cruising the avenue. The clientele was Black and white, including a parade of Hollywood celebrities.

"It was the only integrated setting in Los Angeles," Isoardi wrote. "All races and classes gathered in the clubs, from longshoremen to Pullman porters to Humphrey Bogart, Ava Gardner and Howard Hughes."

Years later, Pepper would recall in his autobiography Straight Life, "It was a beautiful time. It was a festive time. As you walked down the street you heard music coming out of every place. And everybody was happy."

Club Alabam. Photo credit: Los Angeles Public LIbrary

The hottest club on The Avenue was the Club Alabam, next door to the elegant Dunbar Hotel. The Black-owned Dunbar had opened as the Somerville Hotel in 1926 as one of the few hotels in L.A. where Blacks could stay and the only luxury one.

"The Club Alabam was where everybody would go when they left their Hollywood jobs, Beverly Hills jobs, and whatnot. Around about 2 a.m, everybody came from all over everywhere, and they always gathered right in the Club Alabam," said drummer William Douglass in the oral history, Central Avenue Sounds.

The Lincoln Theater opened the same year as a venue for all kinds of entertainment. Movies. Dancing. Music. Chorus lines. Comedians.

Central Avenue had it all.

"To me, Central Avenue was the heart and the focal point of existence. That was the street,' said saxophonist Jack Kelson, a native of L.A. "Everything that happened that was important happened on that street. Almost anybody of importance would have been on Central Avenue if they were in town. It was certainly the main street of my life. It was a complete street with the extra veneer of that mysterious glamour that you didn't find anywhere else."

Dexter Gordon, saxophonist (left) and Charles Mingus, bass (right.) Photo credit: Tom Marcello

In the 1930's, the Central Avenue neighborhood wasn't prosperous. For the most part, Black people, even with a college education, couldn't get high-paying jobs. But most people in the Central Avenue community worked and nearly one third owned their own homes, which was rare for African-Americans in cities. Most of the shops and stores were owned by whites, but many were Black-owned, but, thanks to a campaign by the publisher of the Los Angeles Sentinel, one of two local Black newspapers, many of the white-owned businesses began hiring Black employees.

When World War Two came, defense industry jobs paying good wages drew a flood of Black people from around the country. People were working. Despite the oppressive racial discrimination outside their enclave, within the Black community times were good.

"The clubs were grooving because money was popping. People had plenty of money," saxophonist Cecil "Big Jay" McNelley said in Central Avenue Sounds.

I made my way down Central Avenue in light traffic, armed with a list of addresses of some of the once famous jazz clubs of its heyday. Some of the addresses no longer exist. Many of the buildings bearing the old numbers have been replaced. Others have been converted to no purpose and are barely recognizable.

The Lincoln Theater is now a church

I stopped across the street from the old Lincoln Theater. After it closed as an entertainment venue in 1961, it became in succession a church, a mosque and, its latest incarnation, the Iglesia de Jesucristo Ministerios Juda, with services in Spanish.

I passed an address that had once been Local 767, the Black musicians union. Even the musician unions were segregated then. It was a new building, a car repair shop.

The Dunbar Hotel is now a housing for the elderly

At 46th and Central, I found the old Dunbar Hotel. After years of decline, it's been gutted and modernized to become a retirement home. There's a restaurant and bar on the first floor that serves what it calls "Southern food with an Angeleno Mexico twist." In the corridors, there are blown-up black-and-white images of some of the performers who once stayed and played there. Next door, there is not a trace of Club Alabam.

Central Avenue Jazz Park murals

I crossed Central Avenue and entered a tiny rectangular park with a patch of grass bisected by a curving concrete walkway that led to a wall covered with colorful murals. It was a kind of pantheon of jazz greats. On the black metal fence fronting the avenue hung shirts and blouses, and on the sidewalk bric-a-brac including two dolls in toy strollers. They were being hawked by older Latinas who chatted quietly with each other. A sign nearby identified the little plaza as Central Avenue Jazz Park. It was a modest tribute to a time when this street was the epitome of cool and glamour and excitement, when it was The Avenue, and people would come out to stroll its sidewalks or just hang out, to see and be seen, and to hear some of the greatest music that has ever been created in America. A long, long time ago.

In Part 2, I will examine the decline of Central Avenue and why it happened.

Love this -- and all of your stories Ron. Thank you.

You are a terrific writer w wide-ranging interests and immeasurable curiosity. Did not know this part of LA history, though I had relatives who moved there in the 40's.