Los Angeles's Last Orange Trees

There was once "a sea of citrus" in the L.A. area. The orange became a symbol of California. Now, almost all of the orange groves are gone.

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot

Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone

Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi (1970)

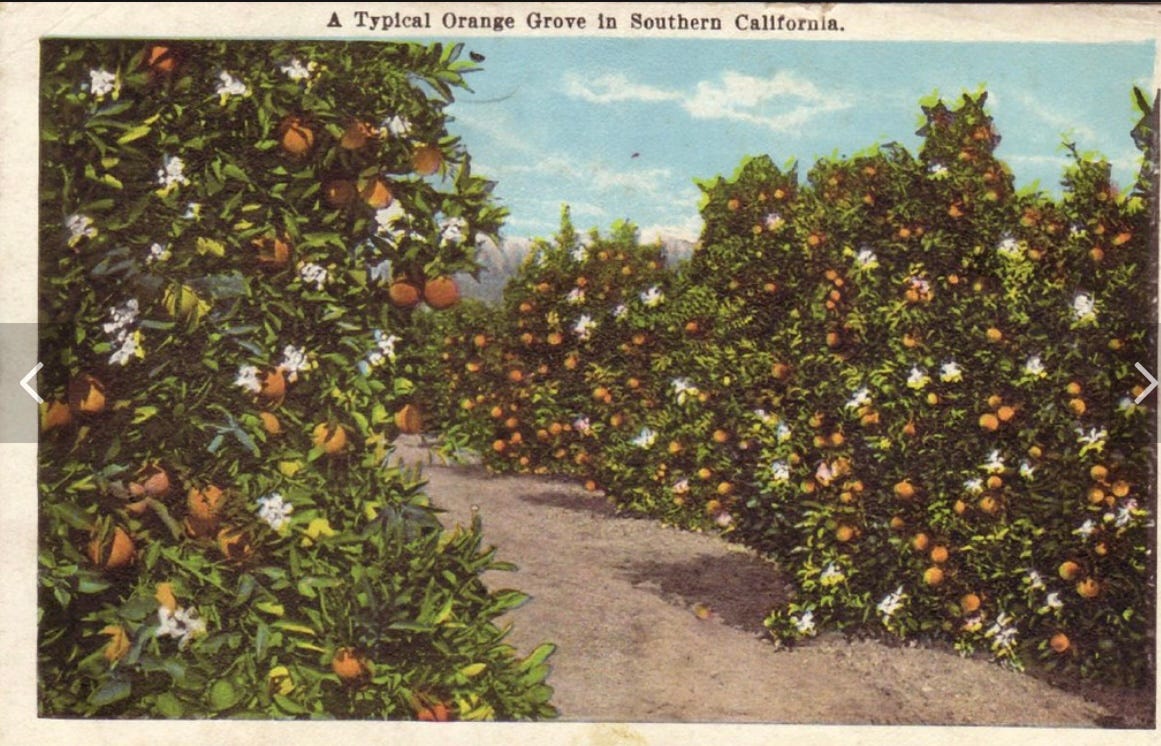

Postcard from when Southern California was America’s “Orange Empire.” photo credit: jasperado

Driving around Los Angeles, you still come across a house with an orange tree in the front or back yard. They’re pretty much all that’s left in an area that not so long ago had so many citrus groves it was known as the Orange Empire.

“They were everywhere,” says David Boule, author of The Orange and the Dream of California.

Orange tree in front yard of a private home

At its peak, there were hundreds of thousands of citrus trees in L.A. County, not to mention tens of thousands of acres of walnut trees, tomato vines and lima beans. But the orange was the king of them all. The orange industry was even bigger than oil. But even more than its economic might, oranges became the very emblem of California.

“The orange was California and California was the orange,” Boule told me. “For 30, 40 years it was the predominant symbol of California and California abundance and beauty and health.”

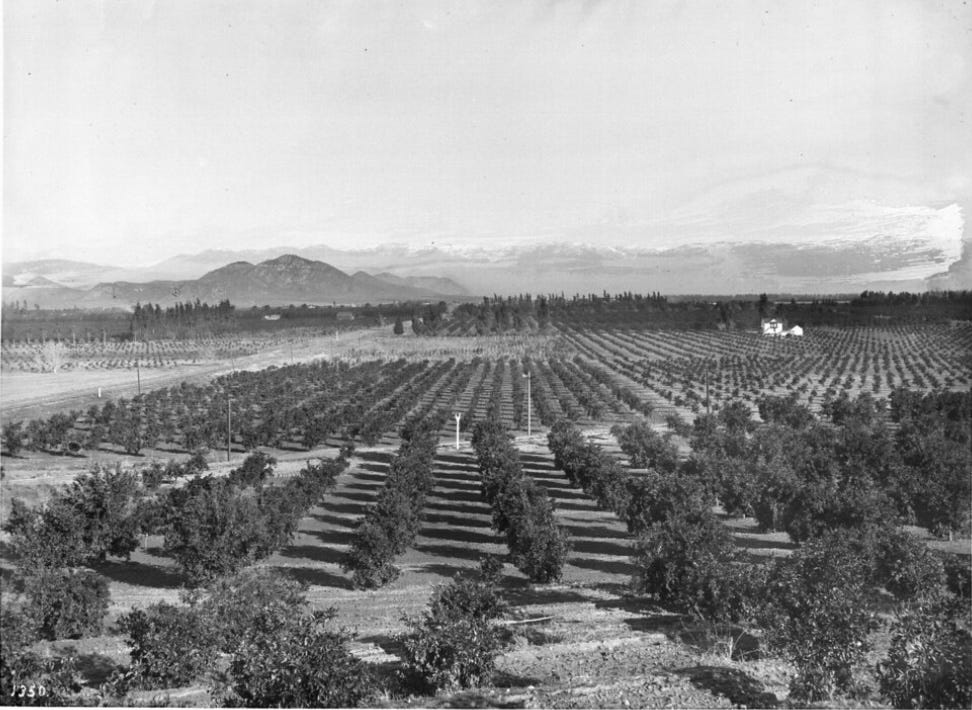

Los Angeles circa 1900. photo credit: fae

L.A. area orange pickers. photo credit: jericl

Like that other iconic symbol of California, the palm tree, oranges were not native to the region. The first Spanish colonists arrived in 1769 and brought with them orange seeds which they planted. But 200 years later, there were still only 8,000 orange trees in L.A. County and 35,000 statewide.

It wasn't until the late 19th century that oranges became a huge business with the advent of refrigerated rail cars that made it possible to ship the fruit east. By 1890, there were over a million orange trees in Los Angeles County alone, including 70,000 acres in the San Fernando Valley.

It didn't last long. Southern California's "Orange Empire" began to wither after the Second World War. As the population of L.A. exploded, land became more valuable as real estate. Orange groves were ripped out and bulldozed over, replaced by houses. The orange industry migrated north to Kern County where it thrives to this day.

By 2023, the only remaining commercial orange grove in Los Angeles was the 12-acre Bothwell Ranch in Woodland Hills in the Valley. Then, last November, over protests by local residents, the Bothwell family sold most of that property to developers. More than 1,100 orange trees will be uprooted to make way for 23 upscale houses. Only four hundred trees will be left standing as ornamentation.

Bothwell Ranch, Woodland Hills

The campus of California State University at Northridge is located only a few miles from Woodland Hills. It's a fairly new college. It opened in 1956 with 2,500 students. Three years later, there were 6,000 students. By 1968, there were more than 15,000. Today, CSUN, as it's known, has an enrollment of 40,000. As the school, it campus gobbled up more and more land, including what had been orange groves.

In the early 1990s, a Geography professor named Robert Gohstand decided to attend a campus planning board meeting. The presenters showed images of how the campus would look in the future. Gohstand noticed there was a parking structure slated to be built at the southeast corner of the campus on the two-acre site of the last of the campus's orange trees.

Robert and Maureen Gohstand. photo credit: CSUN

"The orange grove was gone ... which was a shame," he told me recently. "I took it into my head to launch a battle to save the orange grove."

He wrote a letter of protest to the planning board. The letter became public and began to draw support from faculty and students.

The planning board pushed back. They said the orange trees were rotting and dying. Gohstand researched orange trees and then surveyed each one to assess their condition. They weren't dying. Some of them were just at the end of their natural life span and could be easily replaced with new trees.

Gohstand says he tried "every argument available" in the battle to save the orange orchard. The trees had historical value. They were an important relic of the Valley's agricultural past. The grove was an island of tranquility on the bustling campus.

The faculty senate voted in favor of saving the orchard. The student senate followed suit. The CSUN orange grove was spared.

CSUN orange grove. photo credit: Robert Gohstand

"My objective throughout was always to convert the orange grove into a sort of mother and apple pie symbol which people would leave alone," he recalled. "I must say, I succeeded."

Gohstand is now 88 and a CSUN professor emeritus. Ten years ago, he and his wife, Maureen, helped create a space in the college library devoted to leisure reading that bears their names. I asked him how often he visits the orange grove that he helped to save.

"Every week or two, I'm in or at the edge of it," he said. "Taking a look at how they're doing."

They're one of the remnants of what was once, as the Wall Street Journal described it, a "sea of citrus." Thanks to Professor Gohstand, they're doing just fine.

Thanks for making me aware of something that I once knew about, but never was told what occurred to all those trees. Progress does happen, but sadly erasing so much of our past.