Remembering The First African American West Point Graduate

The "experimental life" of Henry Flipper

Inside the Jefferson Library at West Point are busts of some of America's most famous Army generals. All were graduates of the United States Military Academy, as West Point is formally known. Eisenhower. Pershing. Patton. Bradley. MacArthur. A pantheon of American military greats.

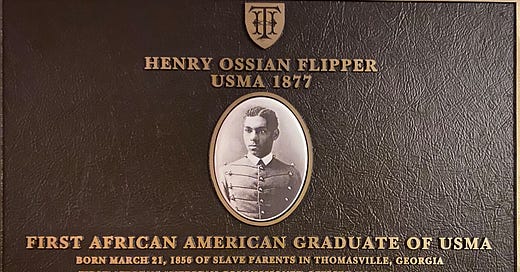

Until it was temporarily removed to be refurbished, there was also in the library the bust of an African-American man who never fought in a formally declared war, who never rose beyond the rank of second lieutenant, whose Army career lasted less than five years and ended in him being thrown out of the Army. Yet today he is honored because of what he endured, overcame and achieved. His name is Henry Ossian Flipper and, in 1877, he was the first African American cadet to graduate from West Point.

This is the story of his rise, fall and, years after he died, the restoration of his reputation and acknowledgement of the trail he blazed; an unfinished trail.

Photo credit: Granger

Henry Flipper was born a slave in Thomasville, Georgia. In one way, he was more fortunate than many other slaves. He and his four siblings were raised by and lived with both parents. Flipper was also allowed to be educated.

After the Civil War, during Reconstruction, he managed to secure an appointment to West Point from a white Georgia congressman, who had once owned slaves. In 1873, young Flipper headed north to West Point where he would be one of five African American cadets, two of whom had entered the Academy ahead of him. Of them, only Flipper would finish.

In The Colored Cadet at West Point, one of two autobiographies he would write, he described his trepidation as he left his home and headed north, "With my mind full of the horrors of the treatment of all former cadets of color, and the dread of inevitable ostracism, I approached tremblingly yet confidently."

His apprehension was warranted. The next four years would be an enormous ordeal and test of his character and determination. The racism he would face would be raw and ugly.

"For him to even be there is nothing short of remarkable," says Quintard Taylor, professor of African American Studies at the University of Washington. "The U.S. Army was reflective of every other major institution in the country at the time. They were not just segregated, they all believed in white supremacy."

Upon arrival at West Point, he received a letter from James Smith, the first black cadet who had come there just a year or two earlier. Smith warned him about what he would experience and offered advice how to survive. Smith would be gone soon afterward because of academic deficiencies.

Over the next four years, Flipper was subjected to vile epithets, isolation and discrimination from white cadets.

Reading Flipper's account of his West Point years, I was struck by his forbearance. He was practically stoic. He wrote that he didn't even care if the white cadets wanted nothing to do with him. That was their choice, he said. What disturbed him was the hypocrisy of those who, literally under the cover of darkness, would be friendly to him and then cruelly ridicule him in front of the other white cadets.

One white classmate came up to Flipper while he was standing post late at night. "We stood and talked quite awhile," Flipper wrote. "He expressed great regret at my treatment, hoped it would be bettered, assured me that he would ever be a friend and treat me as a gentleman should. Another classmate told me, at another time, in effect the same thing... They not only never fulfilled them but treated me even as badly as all the others. They both called me 'n----r' or 'd-----d n----r" [as Flipper wrote it] as suited their inclination."

Despite the pressure, abuse and isolation, Flipper made it to graduation in 1877, sailing through his final oral exams. It was a tremendous accomplishment.

“They had been years of patient endurance and hard and persistent work, interspersed with bright oases of happiness and gladness and joy, as well as weary barren wastes of loneliness, isolation, unhappiness and melancholy,” he wrote. “It had been a sort of bittersweet experience, this experimental life of mine.”

“West Point graduates were elite for the entire society,” says Professor Taylor. “They were looked upon somewhat like corporate heads. They were looked upon like wealthy people in the community. They ranked in that category certainly in the 19th century.”

Flipper never got to enjoy that exalted status. Officially, he may have joined the Long Gray Line of West Point graduates, but he was also officially a Black man in late 19th century America. He was an officer, yes, but commanding and giving orders to white soldiers was out of the question. In fact, no African American officer would be permitted to do that for another 70 years.

With such limited opportunities, Flipper was sent west to lead the only troops a black Army officer could: the 10th Cavalry, the famous Buffalo Soldiers, black soldiers, on the frontier. At first, things went well, as he distinguished himself as a troop commander in engagements with Native Americans, and for his engineering projects including a water drainage system that alleviated malaria at a fort in Oklahoma.

But in 1880, while serving as quartermaster at Fort Davis in Texas, Flipper was accused of embezzling $2,000 and then lying to cover it up. Some historians assert his real “crime” -- what made him a marked man -- was his close friendship with the daughter of his white commander at a previous post in Texas. The post commander was a mentor and friend to Flipper. But other white officers took notice and took offense. The word apparently spread.

“He had gone riding with the daughter of the post commander and this was just unacceptable,” says Quintard Taylor. “I think that’s where Flipper got into trouble more than anything else.”

Flipper ended up being acquitted of the embezzlement charge. But he was convicted of conduct unbecoming of an officer and gentleman. In my research, I could find no explanation for that peculiar outcome. Cleared of the embezzlement charge, yet convicted of unbecoming conduct? In any event, his fate was sealed. Flipper was dismissed from the Army in 1882.

Out of the Army, he remained in the Southwest working as a civil engineer, and then in the oil business in Venezuela (he spoke Spanish). Later, he became an advisor on Mexican affairs to a Senator and Cabinet member.

For the rest of his life, Flipper tried to get his court martial conviction overturned. He never succeeded. In 1940, retired and living in Georgia, he died at the age 84. But that would not be the end. In 1976, his descendants and supporters convinced the Army to change his dismissal status to a good conduct discharge. And in 1998, President Clinton pardoned Flipper.

In 1976, West Point -- where he had been hazed and ignored and slighted -- recognized Flipper by instituting an annual award in his name for the graduating senior exhibiting “leadership, self-discipline and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties.”

“I think you could argue that Henry Flipper knew his opportunities weren’t going to be the same,” Professor Taylor told me. “But you can also argue that he was paving the way for other people.” Taylor likened him to Jackie Robinson.

In 2020, the incoming freshmen class at West Point included 214 African Americans out of 1,240. Until the mid-20th century, there had been a total of 4 black cadets who graduated from the USMA.

And yet.

In 2020, nine black West Point alumni wrote a letter to the academy’s administration alleging that “systemic racism continues to exist” at the academy and issued a 40-page policy proposal with steps to address it. The report contained numerous accounts of alleged racist incidents directed at black cadets.

"The United States Military Academy has not taken the necessary strides towards uprooting the racism that saturates its history," the letter stated.

The Inspector General at the academy vowed to investigate.

I visited West Point the other day, a sparkling mid-summer afternoon. Entering through the main gate, you immediately come upon Buffalo Soldier Field, a huge expanse of grass. The Academy is steeped in tradition and military glory. Duty, Honor, Country is its motto. Cadets greet civilians with deferential sirs and ma’am’s. The views of the Hudson are magnificent. The buildings spotless. Statues of famous generals abound. I saw a few plebes — freshmen — who had arrived only a month ago. AT least some of them destined to be future Army leaders.

I had come hoping to get a sense of the place, a feel for what it must have been like for Flipper, to imagine this young black man there all alone.

In the first of his two autobiographies, Flipper wrote about his determination to go to West Point and succeed against all odds:

“I came to West Point, notwithstanding I had heard so much about the Academy well-fit to dishearten and keep one away. I had set my mind upon West Point and no amount of persuasion, and no harrowing narratives of bad treatment, could have induced me to relinquish the object I had in view.”

Today, West Point has its first African American superintendent in its 218-year history, Lt. Gen. Darryl Williams (USMA, class of 1983), and a black West Point grad, retired four star Army Gen. Lloyd Austin (USMA, class of 1975) is the U.S. Secretary of Defense. Austin was born in segregated Alabama. He was raised in Thomasville, Georgia. Yes, the birthplace and hometown of Lt. Henry O. Flipper.