She was one of the first women architects in America. She designed Hearst Castle. And few people knew her name.

Julia Morgan was the first licensed female architect in California. She designed 700 buildings, but acclaim would only come six decades after she died.

In early December, I visited the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California. I was appropriately awed by the opulence and monumental grandeur of the "Casa Grande," as William Randolph Hearst called it, perched, or perhaps soaring is the better word, atop a ridge with magical vistas of the Pacific Ocean to the west, and the Santa Lucia mountains to the north and east.

The Casa Grande at San Simeon. Photo credit: King of Hearts

The writer Joan Didion once described Hearst's San Simeon mansion as "a sand castle, an implausibility, a place swimming in warm golden light and theatrical mists, a pleasure dome decreed by a man who insisted, out of the one dark fear we all know about, that all the surfaces be gay and brilliant and playful."

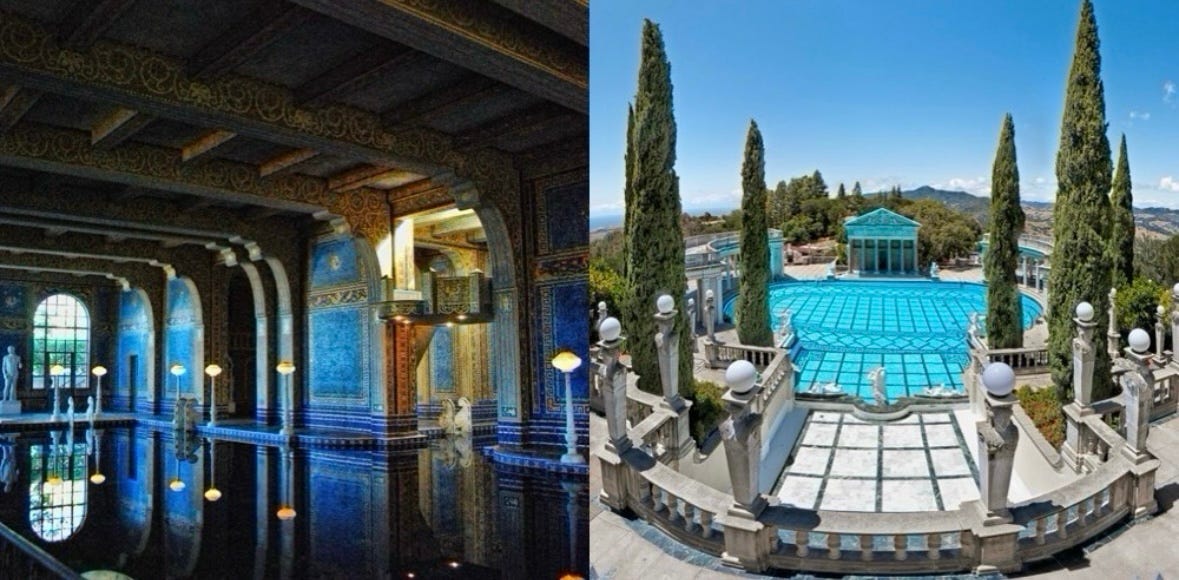

I had been there once before. It was about 30 years ago, but my recollection of that visit was hazy. Mostly, I remembered the enormous dining room with a table that seemed about as long as a football field and which struck me then as extravagant to the point of ridiculous. And I remembered the amazing indoor and outdoor swimming pools. The indoor pool - the Roman pool - is festooned with beautiful azure tiles. Statues of deities and athletes stand sentinel poolside. The massive outdoor - the Neptune pool - is a dazzling marvel with a colonnaded pavilion modeled after a 5th century mausoleum in Ravenna, Italy.

Roman Pool (left). Photo credit: Trish Hartmann. Neptune Pool (right). Photo credit: Kay Gaensler

My tour guide had dutifully told the story of how the property had been bought in the 1860s by Hearst's wealthy father and that the family would camp at the future site of the castle. When his father died in 1919, Hearst, then a 56-year-old media magnate who was fabulously wealthy in his own right, decided he wanted to build a bungalow on the campsite. His original, modest ambition soon expanded. The Hearst Castle would take 28 years to complete and end up encompassing over 100,000 square feet of indoor space.

What I didn't know then and only learned on this recent trip was that the architect of this magnificent palace was a woman named Julia Morgan. I didn't know because no one told me. The tour guide never mentioned her. I would later learn that was not unusual. In 1957, the Hearst Castle property became a state park, Life magazine did a 14-page spread on it. Morgan wasn't mentioned. When DIdion wrote her 1966 essay, A Return To Xanadu, from which I quoted, once again, Morgan's name was missing.

"She never sought fame and she went through a period of being extremely unknown," said Victoria Kastner, author of the 2022 Morgan biography, Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of a Trailblazing Architect.

As the headline on a 1981 ARTnews article about Morgan put it, She Was Considered America's Most Successful Woman Architect - and Hardly Anybody Knew Her Name.

Julia Morgan (1872-1957). photo credit: Special Collections and Archives, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo

Julia Morgan was born to wealthy parents in San Francisco on January 20, 1872. She attended the University of California at Berkeley, where she was one of the first female engineer majors. Fresh out of Cal, she went to work as a draftsman for Bernard Maybeck, a renowned Bay Area architect. It was Maybeck who advised her to apply to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the most prestigious architecture school in the world, which had just started accepting women to study painting and sculpture. She applied three times before she was admitted. Once enrolled, she chose to study architecture.

"They did not say anything about the Department of Architecture, either way, it not entering their heads that there might be women applicants," Morgan would write later to a friend.

Morgan and the few other female students were sometimes harassed by male students who were outraged by the presence of women. Undaunted, Morgan finished in three years. She was woman to graduate from the École des Beaux-Arts. After traveling around Europe, she returned to the Bay Area to set up her own architecture practice in San Francisco. She would become another "first" - the first female licensed architect in the state.

Morgan's practice thrived. She designed hundreds of homes, churches, meeting halls, hospitals, the bell tower at Mills College and dozens of YWCAs. She was also architect for the reconstruction of the Fairmont Hotel following the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire. In her long career, most of her buildings were in California; none farther east than Salt Lake City.

Morgan designed this house in Alameda, California in 1909. Photo credit: Alameda Post

Morgan-designed swimming pool at Berkeley City Club. She designed at least three dozen pools. Photo credit: Kiki

Berkeley City Club. Photo credit: Kiki

Hearst's mother, Phoebe, had come to know and admire Morgan, and introduced her to her only son, William Randolph, in 1908. Morgan designed several buildings for him before he hired her for his most ambitious project at San Simeon.

Morgan tackled the job with her trademark ferocity and determination. She would work on her other assignments five days a week and then hop a train to San Luis Obispo and then travel by car to San Simeon. Working for Hearst might have tried the patience of another architect. He frequently changed his mind about what he wanted even if it was close to completion or, in fact, ostensibly finished. He was constantly coming up with new, expansive ideas. But he and Morgan hit it off and were true collaborators in turning his vision into reality.

"They each brought out the best in each other," Kastner said.

Hearst Castle. photo credit: Special Collections and Archives, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo

Hearst Castle was completed in 1947. Hearst died in 1951 and Morgan, in declining health, retired that same year. She died in 1957. She was 85. During her career, she designed more than 700 buildings. But for decades after her death, she was largely forgotten -- even by the tour guides at Hearst Castle. Only in the 1980s did she begin to gain recognition for her work. Even then, she was still often dismissed by some critics as a mere client's architect. It took many more years before her architecture was fully embraced and appreciated. In 2014, nearly 60 years after she died, she became the first woman to be awarded the American Institute of Architects' Gold Medal, its highest honor.

The legendary American architect Michael Graves, himself an AIA gold medalist, wrote in a letter recommending Morgan for the award, "She designed buildings to fit her clients, blending design strategy with structural articulation in a way that is expressive and contextual, leaving us a legacy of treasures that were as revered when she created them as they are cherished today."

On my recent visit to Hearst Castle, there was an exhibit in the visitor center outlining its history and lots of cool old photos. In the displays, Morgan was prominently mentioned. Among the tour offerings, there was one focused on Morgan and her work there. I took the regular tour but my guide spoke at length about Morgan's work and influence. Julia Morgan is no longer, as Kastner was told by her guide on her first visit in late 1970s, an unknown woman architect.

I recently spoke by phone with Kastner, who began working at Hearst Castle as a tour guide in 1981. She would go on to be its official historian for more than 20 years before retiring in 2018. What follows is a condensed, edited version of our conversation.

Julia Morgan in Paris, 1901. photo credit: Special Collections and Archives, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo

RC: Julia Morgan was a trailblazer, but, aside from blazing a trail for women architects, is she an important architect?

VK: Yes she is. The AIA gold medal was a belated acknowledgment of that. She was the first woman. They'd been awarding it for a hundred years.

RC: How rare were women architects at the turn of the last [20th] century?

VK: In fairness to history, there have probably been a few female vernacular architects through all time. But incredibly rare. There were a few other female architects in America. The best known and kind of initial trailblazer was Louise Bethune (1856-1913) in Buffalo, New York. I'd say there were maybe dozens or more. Bethune had married. Her husband was an architect. He died. She took over the office. That was the typical way [that a woman became an architect then]. Nobody did what Julia Morgan did, which was go to the finest school in the world for architecture, the École des Beaux-Arts - the first woman to be admitted after being turned down, deliberately sabotaged and undergoing all manner of torturous challenges, and then to get her degree in the face of unbelievable obstacles.

RC: Yeah, it sounds like she really was given a hard time at the École des Beaux- Arts, that the male students, maybe faculty too, didn't want her there.

VK: They tormented her. The first time she took the entrance exam, she didn't pass. The second time, she scored worse, and she found out why. The instructors, who were the (admissions) judges, said, "We don't want to encourage little girls" and lowered her score. They admitted women in 1897 and when that occurred, the men rioted. They rioted and chased the women through the streets. The next woman (after Morgan) who graduated from Beaux Arts in architecture graduated in 1923 and she was French.

RC: Back in San Francisco, what did she do to get started? Did she face obstacles?

VK: I think she faced obstacles at every point. She was almost invariably the only woman on any construction site. She was the first licensed female architect in California. She got her license in 1904, the first year it was possible to be licensed... She just found a way. She always found a way.

RC: A criticism directed at her was that she gave in, or accommodated clients, quote-unquote, too much.

VK: Her great mentor, Bernard Maybeck, who was a genius and a far different kind of architect, even he would cut off a client and say, "But this is what I see for you." Like, "I don't care where you want the closet. This is what I see." But I think the evaluation of her as a clients' architect was based, not necessarily as an evaluation of what happened among her contemporaries. She didn't get recognized until the 1980s which was a time when architects were imposing their personalities. I think the "client's architect" term was more a product of the time when she became known, not when she was working. It's kind of astonishing when you think about it. How could that be an objectionable thing when you're hiring somebody? Why would they not want to think about what you wanted?

RC: San Simeon started out a small project and just grew and grew. Was she okay with Hearst constantly making changes and expanding what he wanted?

VK: By then (1919), she had already worked for him and done a major building, the Los Angeles Herald building in downtown Los Angeles. It's not like she didn't know who the guy was. He didn't consider concrete a permanent material in any way. He was constantly changing his mind. She was aware of that. She could have turned him down. She didn't. She told a friend, "He does suffer from a great changeable-ness of mind for which he compensates by allowing me to change my mind now and then."

Morgan designed the three buildings of Hearst’s Wyntoon estate in the Sierras. Photo credit: Bill Tuthill, Tahoe Quarterly

RC: It seems like she worked all the time. Did she ever sleep?

VK: She did not sleep a lot. She was a poor delegator. She didn't have an off button. She was obsessed with her work.

RC: Is there a Julia Morgan style of architecture, an aesthetic that one can point to and say, "This is her style"?

VK: That's another reason she was called a client's architect in the 1980s. It's because you can't look at her work like you can and say, "That's a Frank Lloyd Wright. That's a Frank Gehry." She didn't just do a thing that you could recognize in that sense, no. But I believe there was a Julia Morgan style. It's more about the approach because even if a building is a Tudor, or Spanish, or a very practical hospital, she was always dealing with issues of light and access, practicality, location, scale. It's a different way of looking at a style. It's true that even though I've seen hundreds of her buildings, I wouldn't be able to just point to something and say that's a Julia Morgan building. But that's only about the externals. She had an approach that was unvarying throughout her entire career. It was about how to create buildings that were places where you'd want to spend your life.

Thank you, Ron! I recently joined The Monday Club in San Luis Obispo. The building where we meet was designed by Morgan while she was working on the castle. She was an incredible woman. https://themondayclubslo.org/OUR-HISTORY

Thanks for sharing Julia Morgan's story. I too was unaware of her role until I started planning for my visit to Hearst Castle last May. When I came across her story, I tracked down the book Julia Morgan: An Intimate Portrait of the Trailblazing Architect and read it cover to cover. It was a wonderful discovery! And I was so pleased that not only is she prominent in the Hearst Castle story on the tour now, but that her image was all over the shuttle buses alongside Hearst's when I was there.

Since then, I've been coming across stories of all kinds of pioneering women at the turn of the last century - Natalie Boulanger who worked with some of the century's most well-known composers, Marjorie Post (haven't read the book yet), Kate Gleason of Gleason Works in Rochester, NY, who became a recognized engineer. So many great stories that still need to be told!