The Cost of Freedom: The Life and Death of Sgt. John Basilone PART 1

He was a hero in one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific theater during the Second World War. He was awarded the Medal of Honor and sent home. But he pleaded to go back to the war, and he did.

The original version of this story appeared on Facebook Bulletin in 2022. I am re-posting it as Memorial Day 2025 approaches to remind us all of what that holiday represents other than a day off from work or school.

Find the cost of freedom

Buried in the ground

-- Song by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young

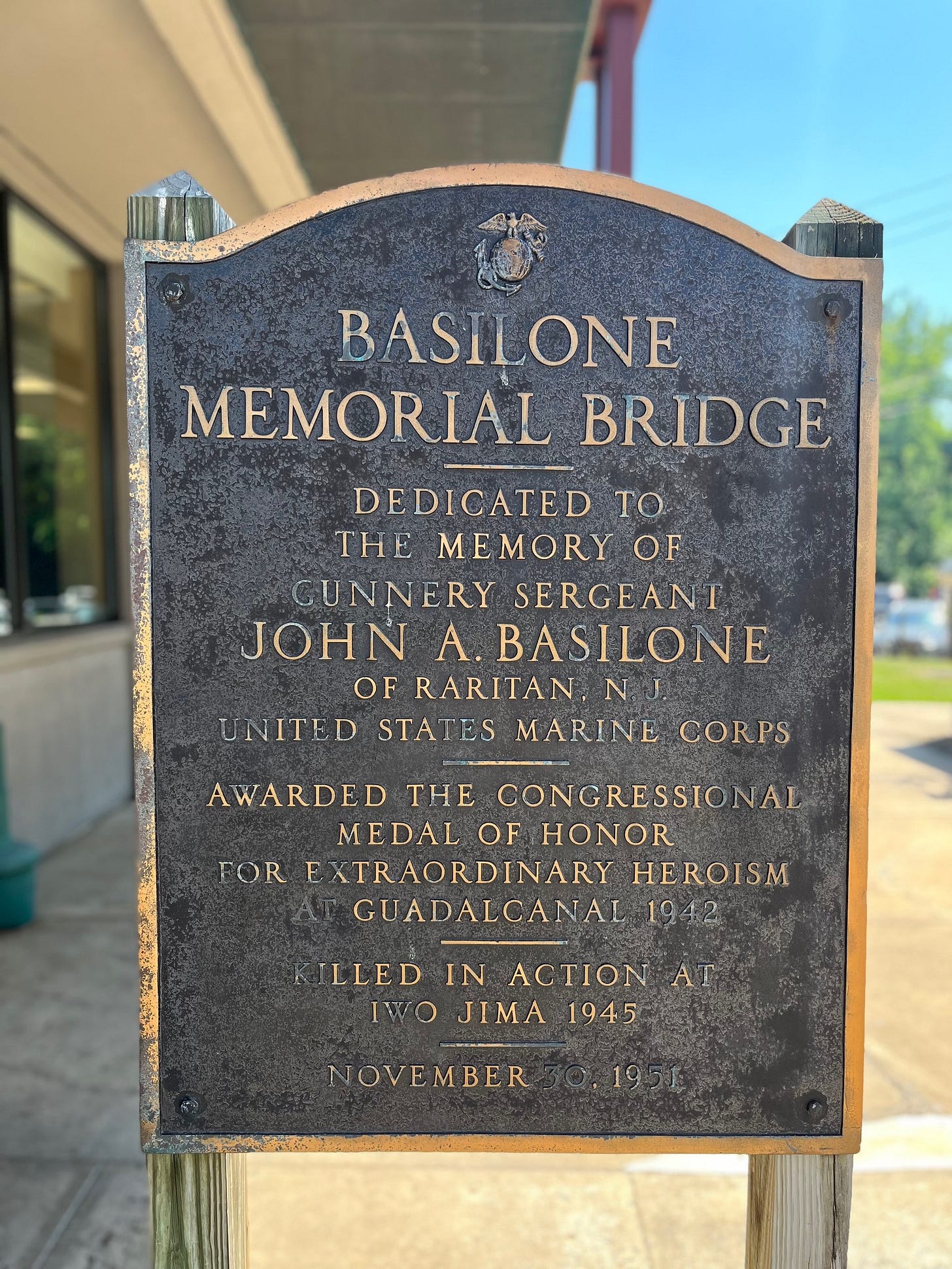

I pulled off the New Jersey Turnpike at the Thomas Edison Service Plaza to get gas and a cup of coffee. When I left the food court, I sipped the coffee and wandering the parking lot, killing time before getting back on the road. Next to the building housing the fast-food outlets and restrooms, there was a small park. In it, there was a large plaque. Curious, I went to see what it was.

This was the plaque:

Photo credit: Ron Claiborne

I wondered, who was John Basilone? What had he done on Guadalcanal that earned him the country's highest decoration for valor? And what happened on Iwo Jima three years later? I wanted to find out.

John Basilone, 1943. Photo credit: Archives Branch, USMC History Division

John Basilone was the sixth of 10 children of Salvatore Basilone, an Italian immigrant, and his wife, Dora. He was born in 1916 in Buffalo, New York but his family moved to Raritan, New Jersey, his mom's hometown, when he was 2. There, his father opened a tailoring shop.

Young John was a popular and mischievous kid with a penchant for adventure. When he was 7, he climbed into a pen with a bull with the intention of taming it. It promptly knocked him down.

He left school after 8th grade and went to work for a while as a caddie at the local golf club and later as a deliverer for a local dry cleaners. When he was just shy of his 18th birthday, he joined the Army. He would spend the next three years posted in the Philippines which earned him the lifelong nickname, Manila John.

When his Army enlistment ended, he returned to Raritan, living with his parents and resuming work in a succession of low-skill jobs. In 1940, he decided to return to the military, this time as a Marine. At some point, he acquired a tattoo that read: Death Before Dishonor.

Marines on Guadalcanal, 1942 Photo credit: Archives Branch, USMC History Division

Starting in the late summer of 1942, the focal point of the war in the Pacific was a tiny island named Guadalcanal, where the Japanese had built up a large force. From there, they could expand their advances throughout the region. The Allies were determined to stop them on Guadalcanal.

Thousands of U.S. Marines landed on the island in early August, taking control of a key airstrip, which they named Henderson Field. For weeks, the fighting raged on the land and sea. Casualties on both sides mounted from the fierce combat, from the almost constant shelling and bombardment, and from disease. The Japanese sent in reinforcements, building up to 36,000 troops by October.

"By late October, a single Marine battalion was all that stood between Henderson Field and two Japanese regiments," according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. One of those Marines was John Basilone.

For days and nights, the Americans were pounded by Japanese artillery, while Japanese soldiers moved closer to prepare for their assault. On the night of October 24th, they attacked.

Basilone's troops were dug in on a ridge about 1,000 yards from the airfield. Japanese soldiers came at them in waves, taking and inflicting casualties until only Basilone and a few of his men were left alive and in action. They had their sidearms and just two functioning heavy machine guns. When their machine gun ammunition ran low, Basilone took off, running and crawling under heavy fire, to get more and bring it back. When that ran low, he did it again, and then took charge himself, firing the heavy weapons, rolling from one to the other.

"At one point, Basilone lost his gloves, which were essential hand protection when swapping out scalding hot barrels for high powered machine guns. But that didn't stop Basilone, who used his bare hands to continue to operate the blistering gun and single-handedly eliminate an entire wave of Japanese soldiers while burning his hands and arms," according to one account.

It went on like this for days.

Pfc. Nash Phillips, who was with Basilone, described it later, "Basilone had a machine gun on the go for three days and nights without sleep, rest or food. He was barefooted and eyes were red as fire. His face was dirty black from gunfire and lack of sleep. His shirt sleeves were rolled up to his shoulders. He had a .45 tucked in the waistband of his trousers."

Photo credit: Ron Claiborne

Outnumbered, outgunned and almost out of ammunition, the Marines somehow held the line. The Battle of Guadalcanal would later be seen as the key turning point in the War in the Pacific.

In a typewritten biography of Basilone in a notebook I was shown at the Raritan public library, he's quoted saying that when when battle was finally over, "I rested my head on the edge of the emplacement, weary, tired and thankful that the Lord had seen fit to spare me."

The biography says memories of the carnage would haunt Basilone. Sometimes he would wake up screaming. He was 26 years old.

Photo credit: Raritan, N.J. Public Library

In the spring of 1943, Basilone was awarded the Medal of Honor. He was grateful, but he couldn't quite understand why he had been singled out for the decoration.

"Only part of this medal belongs to me," he once said. "Pieces of it belong to the boys who are still on Guadalcanal."

In the spring of 1943, Sgt. Basilone received new orders: to return to the U.S. His new assignment would be touring the country, promoting war bonds. Who better for that than a war hero? His exploits had been splashed across the front pages of newspapers. He was profiled in Life magazine; his image splashed on the cover of Colliers. He was featured in newsreels. Handsome and single, he was showered with marriage proposals.

Raritan public library poster, Photo by Ron Claiborne

Basilone embarked on a whirlwind tour, going from city to city, appearing at fundraising events. He wasn't much of a speaker, but it didn't really matter. He was genuine and modest, and his heroism was a compelling story.

Photo credit: Raritan Public Library

In September 1943, he returned to Raritan where the town -- his town -- pulled out all the stops to pay tribute him. On September 19th, John Basilone Day, he was feted with a parade that drew an estimated 30,000 people along the route.

Basilone spoke only briefly. "Today," he said," is like a dream to me."

Lifelong Raritan resident Peter Vitelli, 7 years old at the time, was there.

"I knew it was something special," he told me by phone. "I remember John riding in an open convertible with his parents. They paraded him down Main Street. I remember every little detail, I really do. It was a glorious day. It really was."

After John Basilone Day, he was soon back on the war bond campaign, roaming the country, often accompanied by Hollywood actors and actresses. He was now far, far away from the steaming jungle, death and horrors of Guadalcanal.

But Basilone never enjoyed all the attention and was increasingly discomfited by it. The biography in the Raritan library says he would privately complain about being a "museum piece." The military offered him an officer's commission. He declined. They offered to make him a gunnery instructor stateside. He said no, thanks. What he really wanted, what he was pleading for was to return to the war. The military refused.

"Everyone was trying to give advice, 'Don't go back! Don't go back!" Vitelli said. "He was a warrior. He wanted to get back into the fight."

He would get his wish.

Part 2 of this story will post on Memorial Day, Monday, May 26

Such bravery - and commitment. I learned so much - thank you!

Looking forward to the follow-up story!!!