The Last Time the U.S. Attempted the Mass Deportation of Undocumented Migrants

In early 1950's, the Eisenhower Administration cracked down on Mexicans in the U.S. illegally, and deported hundreds of thousands of them. Officials said it "solved the problem." It didn't.

“Dwight Eisenhower, good president, great president, people liked him ... I like Ike. Moved a million and half illegal immigrants out of this country... moved them way south. They never came back. Dwight Eisenhower. You don't get nicer. You don't get friendlier.”

Donald Trump, 2015

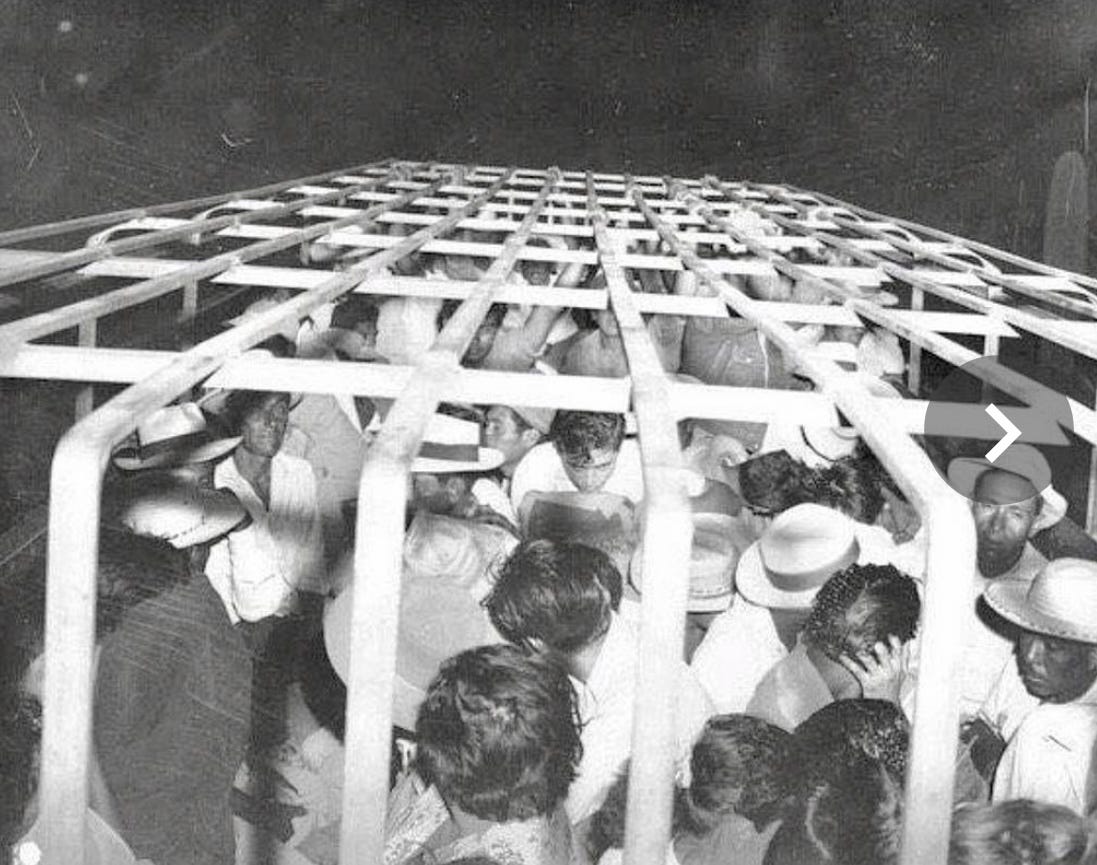

Detainees awaiting deportation in El Centro, California, 1954. Photo credit: Larry Sharky, Los Angeles Times

The Eisenhower Administration's deportation effort about which President Trump spoke with such glowing admiration ten years ago is the blueprint for what he's doing now, but on an even larger scale. Will it succeed? Operation Wetback, as the Eisenhower era program was called, invoking a slur referring to Mexican immigrants, rounded up hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and sent them back to Mexico. It would be the largest mass deportation of undocumented migrants in the history of the United States. It solved nothing.

The impetus for Operation Wetback was an economic slowdown in the early 1950s which led to a growing popular sentiment that "illegal aliens" were taking jobs away from Americans. Organized labor too saw undocumented workers as a threat to union workers by depressing wages. And racism was no small part of the equation. There were lots of people living in the U.S. illegally, but Operation Wetback was concerned with only one particular group. Mexicans. Public officials and newspapers railed about an "invasion" of Mexicans. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Attorney General Herbert Brownell blamed the immigrants not just for displacing American workers but "spreading disease and contributing to crime rates."

Detainees boarding buses to be returned Mexico. Photo credit: Texas AFL-CIO, Mexican-American Affairs Committee Records, University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections

In the spring of 1954, Joseph Swing, a former Army general and the newly appointed commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, redeployed hundreds of Border Patrol officers and resources from the East Coast and the U.S.- Canada border to the Southwest to track down and deport Mexicans who were in the country illegally. What ensued was what UCLA historian Kelly Lytle Hernandez says was "not just mass deportation. It was mass racial banishment."

Mexican “braceros.” Up to 5 million workers entered the U.S. as legal seasonal workers 1942-1964. Photo credit: Oregon State University

Until early in the 20th century, the U.S.- Mexico frontier was more of a theoretical line on a map than a real border. Mexicans easily crossed back and forth, working for a while, mostly as seasonal farm labor in California, Texas and Arizona. Most would return to Mexico after the fall harvest and do it all over again the next year. Some chose to stay in the U.S.

In the 1920s, popular opinion turned against immigration generally, legal and illegal. Congress passed the National Origins Act of 1924 that set quotas for people from Eastern and Southern Europe and banned Asians altogether. The U.S. State Department openly admitted the purpose was to "preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity."

Nativists were a powerful political force, and they began clamoring to similarly restrict Mexican immigration. But they ran into a powerful opponent: agribusinessmen in the Southwest and West who depended on Mexican workers for cheap labor.

The head of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce said, "We are totally dependent ... upon Mexico for agricultural and industrial common or casual labor."

A California rancher named Fred Bixby, testifying before a Senate committee on immigration in 1928, put it more rawly: "We have no Chinamen. We have no Japs. The Hindu is worthless. The Filipino is nothing, and the white man will not do the work."

In the end, a compromise was reached that satisfied the Nativists and agri-business. The Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929 made unauthorized entry or reentry into the U.S. a crime for the first time. That way, the agricultural industry could legally import Mexican workers as needed by providing them with work permits. Notably, under the Act, overstaying a visa - which was how many Europeans got into the country illegally - was not covered.

Things changed with the Second World War. Millions of Americans were called to military service, creating a drastic labor shortage for U.S. farmers. Suddenly they were desperate for workers. To help, the Roosevelt Administration negotiated with Mexico what was called the Bracero Program that authorized Mexicans to enter the country as seasonal farm workers. It was limited to men with agricultural skills. By the time the program ended in the 1964s, an estimated 4 million to 5 million Mexican workers had worked in the U.S. under it.

Operation Wetback officially began in California on June 9, 1954, and spread quickly within California and Arizona. In July, it expanded to the Rio Grande Valley in Texas where there was no Bracero Program because Texas farmers bristled at the official requirement of paying a minimum wage and providing sanitary living conditions. The raids would eventually spread to parts of the Midwest as agents swept through farms, parks, neighborhoods, hotels and restaurants in search of illegal immigrants, which often amounted to accosting anyone who appeared to be Hispanic.

"Border agents' tactics included descending on Mexican-American neighborhoods, demanding identification from 'Mexican-looking' citizens on the street, invading private homes in the middle of the night, and raiding Mexican businesses," according to a history on the website of the Equal Justice Initiative. "Without a hearing or oversight, agents often seized people who were lawfully in the country."

Sometimes, detainees were immediately "paroled" to become legal braceros on farms. More often, they were kicked out of the country even if they had a spouse or children who were American citizens..

Joaquin "Jack" Sanchez, a Chicago attorney, told the Washington Post, his grandmother, Aurora, who lived in Texas with her American-born husband and American-born children, was arrested in 1954 and given just a few minutes to gather her belongings. She and her infant daughter, Noelia (Sanchez's mother) were left to fend for themselves in Reynosa, Mexico, Sanchez said. They returned to the U.S. two years later.

Photo credit: Border Patrol Museum

The conditions many detainees endured were brutal. They would first be taken to holding camps, where some were held in caged pens. One Mexican labor leader said they were packed like cattle in the trains and trucks that brought them to Mexico. Columbia University historian Mae Ngai said 88 people died of sunstroke after being held in 112-degree heat. For a while, people were deported on boats whose conditions, according to a Congressional committee's report, resembled those of an 18th century slave ship. The ship deportations ended after seven detainees drowned on one voyage.

Once they reached the border, some of the deported Mexicans simply crossed back into the U.S. again. So Mexican authorities, who were cooperating with the U.S., began transporting them further into Mexico to make it harder for them to reenter the United States. Many did anyway.

How many people were deported and/or self-deported is impossible to know. But there is evidence that more than 800,000 people were deported in the period 1952 to 1954 (The effort to hunt down and remove undocumented migrants actually began before Operation Wetback was announced.) But in the fall of 1954, funding for the special operation began to dry up. Apprehensions immediately plunged.

"They just stopped arresting people," said Hernandez.

Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1954.

Officials cited the steep decline in number of apprehensions as proof of the operation's success, and declared the problem solved.

"Operation Wetback stemmed an actual invasion by illegal entrants from Mexico," Attorney General Brownell told a Congressional committee in 1956. "The border areas and the large industrial centers where illegal entrants often made their way are wholly relieved of the wetback problem."

And that was how a credulous and approving press reported it.

"Today the main result of Operation Wetback ... is far-reaching, that is that the Mexican wetback has been virtually erased from the scene," the Los Angeles Times article said in June 1955 on the anniversary of the operation.

Victoria DeFrancesco Soto, a political science professor at the University of Texas, said, "From a media relations perspective, Operation Wetback was a success. The optics of the large-scale apprehensions was a success. Public discontent was largely appeased. But from a policy perspective, Operation Wetback failed. Soon after, immigration from Mexico into the United States picked up. The core demand of Mexican labor was never addressed."

Today, there are an estimated 11 million people living in the United States illegally, many more than 70 years ago. Trump says he can and will deport them, just like Ike did.

Thanks for another clear history lesson - an episode I didn’t know about ( OK, we were toddlers at the time, but still…). And in the end, the solution was to say ,” Problem solved” and pretend it was! Our Orange Overlord has learned from a master!